There is a specific kind of tension that hangs over the final bit of free testing in any sport. It is the tension of running out of sanctioned preparation time, of knowing that the next time these cars roll out of the garage, the points will be real and the errors will be permanent. In Formula 1 in 2026, that tension arrived early, because the regulations are so new and the competitive picture so genuinely opaque that nobody, not even the people closest to the data, seems fully willing to claim they know who will win the first race in Melbourne on March 8.

Wednesday’s opening day of the second and final Bahrain test did not resolve that uncertainty. What it did was give it shape. Mercedes looked composed, fast, and progressive. Ferrari looked technically ambitious but operationally frayed. McLaren was quietly, efficiently threatening. Red Bull had a rough morning and a determined afternoon. And Aston Martin, for the second week in succession, spent more time trying to solve problems than creating them.

George Russell finished fastest with a 1m33.459s, a new benchmark for all of pre-season. But the lap time, as everyone in the paddock will tell you with varying degrees of sincerity, barely scratches the surface of what this day actually meant.

The Bahrain International Circuit sits in the desert outside Sakhir, about 30 kilometres south of Manama, and it has hosted pre-season testing repeatedly over the years precisely because its relatively predictable conditions, its multi-surface asphalt that produces meaningful tyre data, and its combination of high-speed sweeps, technical chicanes, and long straights make it a comprehensive examination for any new car. The track runs 5.412 kilometres per lap. Under the 2026 test regulations, running was scheduled between 9 am and 6 pm local time with a one-hour lunch break, giving each team a maximum of eight hours of competitive running.

Unlike the first Bahrain test a week earlier, the second was fully live on both F1TV and Sky Sports F1 from lights out to chequered flag, not just the final hour. That meant the cameras were rolling, the commentary teams were active, and the teams were on notice that every decision they made, from which tyre compound to run to which driver to send out first, would be visible and analysable in near real-time. Whether that visibility changes behaviour is debatable, and teams are always quick to deny it, but the simple fact is that things happened on Wednesday that did not happen at the first test, and some of those things happened in front of a significantly larger audience.

After the five-day Barcelona shakedown in January, conducted behind closed doors, and the first three-day Bahrain test from February 11 to 13, ten of the eleven teams arrived at the second test with six full days of running under their belts. The cars were no longer debutants. The teething troubles, or at least the first generation of them, had mostly been identified if not always resolved. The second test was supposed to be where teams shifted from basic reliability validation towards performance understanding, tyre management programmes, race simulation runs, and the kind of short-stint qualifying simulations that give onlookers the most misleading possible view of who is actually quick.

It mostly delivered on that premise, with the inevitable interruptions.

Charles Leclerc emerged from the Ferrari garage before 10 am on Wednesday and immediately gave everyone something to look at. Not the lap time, though that came quickly enough, but the rear of the SF-26 itself. Nestled behind the exhaust tailpipe was a small winglet that had not been present on the car the previous week, an aerodynamic element positioned in a region where regulations impose severe constraints. Ferrari’s engineers had worked around those constraints in a way that had clearly been planned from the very beginning of the car’s design rather than bolted on as an afterthought.

The technical detail matters here. The regulations allow a wing profile to be positioned up to 60 millimetres from the rear axle centreline in that part of the car. Normally, that constraint prevents any meaningful device from sitting beyond the end of the exhaust pipe. Ferrari’s solution was elegant and, crucially, non-replicable without a fundamental redesign of a rival car’s rear end: they moved the differential as far rearward as possible within the deformable structure, creating space in which the new winglet, internally designated as FTM, could sit. The wing connects directly to the diffuser’s upper trailing edge, reportedly helping to keep the diffuser’s airflow planted at higher rear ride heights. Former Ferrari race strategist Ruth Buscombe, watching from the F1TV commentary booth, described it live as “absolutely beautiful.”

What gives the solution particular relevance in 2026 is the nature of the new power units. Because the MGU-H has been removed from the new regulations, the V6 engine must increasingly act as an electricity generator, keeping revs elevated even through medium and low-speed corners to charge the battery system. That means exhaust gas flow is far more constant throughout a lap than it was in the hybrid era up to 2025, providing a reliable stream of energy that a correctly positioned wing element can exploit to influence the airflow over the diffuser. McLaren’s Andrea Stella spent what was described as “a long time” studying the back of the Ferrari in the paddock, which is itself a form of flattery.

The independent analysis point here is an important one: because the FTM device works best when exhaust flow is high and consistent, the advantage it provides will be circuit-specific, favouring tracks where the energy management philosophy keeps the combustion engine working hard for longer. At circuits where teams can coast or heavily harvest electrical energy through slow corners, the device’s benefit will be diminished. Whether this makes it a decisive weapon throughout a 24-race season or merely a clever tool for specific circuits is the real question Ferrari will be trying to answer in the remaining test days.

Leclerc’s morning session with the FTM-equipped SF-26 produced the fastest time of the morning, a 1m33.739s. Put that number in context: it was faster than anything Lewis Hamilton, Russell, Piastri, or any of the four-car big-team drivers had managed at any point during the entire first Bahrain test a week earlier, where Antonelli’s session-topping 1m33.669s on the final day had been the absolute benchmark. Leclerc was only 0.070s off that benchmark on a fresh day with fresh track conditions, and with a car that had received significant upgrade work between tests. That alone tells you that Ferrari’s development direction is working.

Red Bull, meanwhile, was having exactly the kind of morning they could have done without. Isack Hadjar climbed into the RB22 early in the session and immediately ran into a water system problem that restricted him to just 13 laps before the lunch break. The exact nature of the water issue was not disclosed, but it was understood to be separate from the hydraulic leak that had hampered the car in the first Bahrain test, which means Red Bull was dealing with a second reliability fault in successive tests, in two distinct systems. For a team whose power unit manufacturer, Red Bull Powertrains, in partnership with Ford, had been considered reliable if not spectacular during the first test, losing more track time to component problems was a growing concern.

The absence of Max Verstappen from Wednesday’s running was part of a deliberate plan: Hadjar would drive on days one and three, Verstappen would take day two. Given Hadjar’s compromised morning, however, the net result was that Red Bull accumulated very little meaningful data from the first session on a day when every other top team was building up their picture of the car. Hadjar sat trackside for extended periods of the morning, watching other teams set faster times around a circuit he was unable to use.

The driver’s swap at lunch changed the character of the afternoon entirely. George Russell took over the Mercedes, Oscar Piastri replaced Lando Norris at McLaren, Lewis Hamilton climbed into the Ferrari from Leclerc, and the afternoon promptly produced a sequence of incidents and problems that reminded everyone why pre-season testing is never dull.

Ferrari’s screens went up in front of their garage within the first 90 minutes of the afternoon session. The tall white screens that teams erect to block spectators and rivals from seeing what they are working on in the pit lane are a familiar signal that something unplanned is happening. The Maranello crew worked on Hamilton’s SF-26 for an extended period, the seven-time champion sitting patient and apparently unruffled in his seat or standing nearby watching his engineers diagnose whatever the issue was. By the time Hamilton rejoined the session, he was carrying additional flow-visualisation paint on the car’s floor, which suggested Ferrari had used the enforced garage time to apply flo-viz for data collection, turning a problem into something at least partially productive.

Hamilton ultimately completed 44 laps across the day, compared to Leclerc’s 70 in the morning session alone. Two separate stints of over 20 minutes in the garage gave him the lowest lap total of any of the eight drivers across the four top teams. The 44 laps he did complete were enough for seventh overall with a 1m34.299s, but the shortfall in running means Ferrari’s understanding of the car’s balance across a full afternoon was more limited than they would have liked 18 days before Melbourne.

The numbers tell their own quiet story here. Look at the mileage data from Test 1 and compare it to Wednesday’s Test 2 numbers, and you notice something instructive: throughout the first test, Hamilton accumulated a total of 202 laps across his three sessions. Russell, by contrast, managed only 188 in that same test, partly because Mercedes’ own reliability issues had clipped his running on day two. Both men arrived at the second test carrying something to prove about mileage, and Russell’s 76-lap total on Wednesday partially addressed that. Hamilton’s 44-lap total, through no fault of his own, extended the pattern in the wrong direction.

The afternoon’s most dramatic moment arrived early, when Lance Stroll’s Aston Martin went off the circuit at Turn 11, the tightening left-hander that catches out drivers who arrive with too much speed and too little rotation. The AMR26 appeared to lose drive as Stroll downshifted through the gears on the approach, the car becoming a passive object rather than a driven one and sliding helplessly into the gravel trap. The red flag was called, the session paused, and the car was recovered without serious damage to either machine or driver.

Context matters enormously for this incident. Turn 11 at Bahrain is one of those corners where the 2026 cars’ energy management creates a specific challenge: as the MGU-K switches between harvest and deploy modes through the braking phase, there is a transient change in the car’s behaviour at the rear that drivers must account for in a way that has no equivalent in the previous generation of power units. Whether that contributed to Stroll’s spin, or whether it was a more straightforward loss of power from the Honda engine, was not confirmed. But the AMR26 losing drive under braking is consistent with something going wrong in the power unit or drivetrain systems, rather than a simple aerodynamic failure.

Stroll and Fernando Alonso combined for just 54 laps on Wednesday. That was the lowest joint team total of any constructor, five fewer even than the Cadillac pair of Valtteri Bottas and Sergio Perez, who operate as an entirely new entry still learning the basic fundamentals of a Formula 1 circuit at race pace. To be doing less mileage than the newest entrant to the sport is not where a team with Aston Martin’s ambitions and resources, not to mention the design input of Adrian Newey, wants to be at this stage of the pre-season.

Against the backdrop of rivals’ troubleshooting and incident management, Mercedes ran a textbook afternoon that was so smooth it was almost unremarkable, which in testing is the highest form of praise.

The upgrade package Mercedes had brought to this second test was substantial across the full breadth of the car. The sidepod profile had been reworked to be more compact at the rearward section, with a new directional vane on the sidepod’s upper surface just behind the mirror stay, designed to work in conjunction with a new hot air radiator exit that had also been introduced. The floor was revised at the rear corner, with what appeared to be a turning vane replacing the inlet louvres previously used to connect the airflow on top of the floor to the so-called tyre squirt region, the turbulent zone near the rear tyre contact patch that every team was trying to manage under the new regulations. At the front, the brake duct was reduced in bulk, and a new front wing endplate incorporated horizontal vanes that had become a common feature of competitive 2026-spec cars.

What is worth noting independently is the confidence that bringing such a package implies. A team that is uncertain about its car’s fundamental direction does not show up to the last test before a season opener with broad changes across multiple parts of the car. They run what they have and try to optimise it. Mercedes clearly felt that the W17 was in a place where development changes could be built upon and understood quickly, and the fact that they ended the first test on top and the first day of the second test on top again suggests the confidence was well-founded.

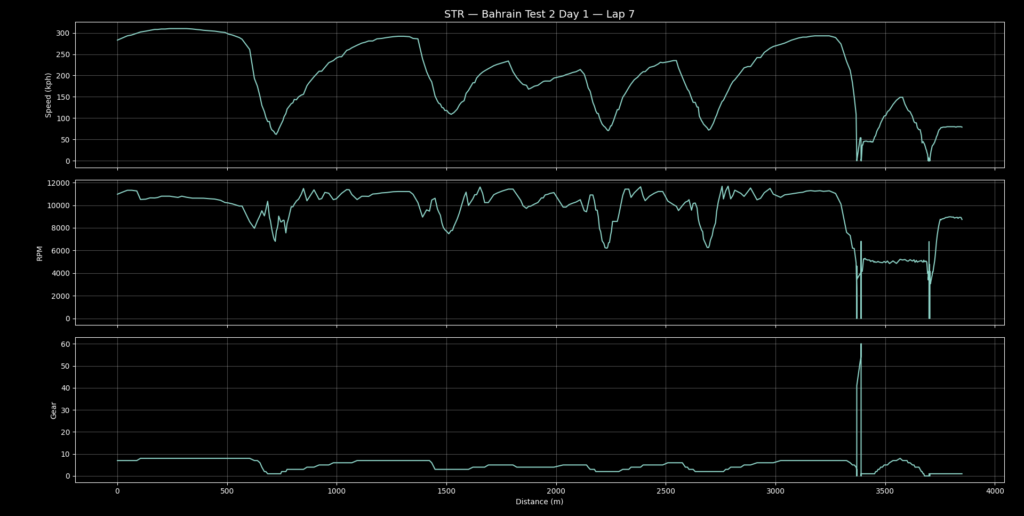

Russell’s afternoon programme was a model of structured testing. He completed a nine-lap long run on C2 (medium) tyres, averaging 1m36.527s across those laps. That is a genuinely informative data point: a nine-lap run that averages better than 1m36.5s suggests the car has real pace over a sustained stint with fuel load, not just on a fresh set of softs for a single flying lap. He then switched to C3 (hard) tyres for a qualifying simulation. The first attempt was ruined by a lock-up under braking at Turn 10, Russell was visibly frustrated as the car ran wide, and the lap was wasted. The discipline to go again on the same set of tyres and find a 1m33.459s on the second attempt was the kind of mental composure that lap-time chasing at testing requires.

That 1m33.459s was the fastest anyone had gone at the Bahrain International Circuit in the entire 2026 pre-season. It beat Antonelli’s 1m33.669s from the end of the first test by 0.210s, and it did so with the track having not rubbered-in significantly overnight and with the afternoon session’s slightly cooler air temperature giving a minor tyre advantage over morning conditions. Piastri was only 0.010s slower at 1m33.469s, a gap so small as to be within the variation of a single tyre temperature delta mid-corner. The top two were essentially identical in outright pace on Wednesday.

Russell’s 76-lap total was not only the highest of the day but significantly above what most drivers achieved. Norris completed 54 laps in the morning before handing over to Piastri, who added 70, giving McLaren a combined total of 124 laps, the second most of any team on the day. Mercedes accumulated 145 laps (76 from Russell, 69 from Antonelli in the morning), while Ferrari’s combined total of 114 (70 from Leclerc and 44 from Hamilton) reflected the afternoon’s garage time.

By mid-afternoon on Wednesday, the most consequential story of the day had nothing to do with lap times. It played out in a meeting room somewhere in the paddock, between representatives of the five power unit manufacturers, the FIA, and Formula One Management, and it concerned a technical dispute that had been building since before the first tyre turned in anger at the Barcelona shakedown in January.

The 2026 regulations reduced the maximum geometric compression ratio from 18:1 under the old rules to 16:1. The compression ratio in an internal combustion engine is the ratio between the volume of the cylinder when the piston is at the bottom of its stroke and the volume when it is at the top. A higher ratio generally produces more efficient combustion and therefore more power. The FIA lowered the limit specifically to create more parity between the established power unit manufacturers, who had been developing their engines under 18:1 conditions for years, and the new entrants, notably Audi and the returning Red Bull Powertrains Ford partnership.

The catch, which became apparent to rival manufacturers during the winter, was that the regulation, as written, specified the compression ratio would be measured at ambient temperature, with the engine cold and stationary. But internal combustion engines operate at extremely high temperatures when running. Materials expand under heat. Piston geometry changes. Clearances tighten. The practical result is that an engine designed to measure exactly at 16:1 when cold can see its effective compression ratio climb significantly when running at operating temperature, potentially approaching the old 18:1 limit that the regulation was designed to leave behind.

Mercedes was identified as having understood and exploited this thermal expansion effect from the ground up in their new power unit design. Estimates of the performance advantage ranged from around 15 brake horsepower at the lower end to figures between 20 and 30 brake horsepower according to Max Verstappen, who is not an engineer but who has spent enough time sitting on top of competitive and uncompetitive power units to have a fairly calibrated intuition. Whether the advantage was precisely 15bhp or twice that, the principle was clear: Mercedes had eight cars on the grid receiving potentially more power than their competitors believed was permitted by the intent of the rules.

Red Bull Powertrains was believed to have arrived at a similar understanding during their development process. That made the politics particularly complex: initially, Red Bull’s Ben Hodgkinson had been relatively relaxed about the matter, describing it as “a lot of noise about nothing.” But by the time the second Bahrain test began, Red Bull had switched positions, joining Ferrari, Honda and Audi in pushing for regulatory clarity. The timing of that switch, whether driven by the realisation that their Ford power unit could not exploit the thermal expansion effect to the same degree as Mercedes, or by other strategic considerations, became a topic of significant paddock discussion.

The FIA’s response, communicated through an official statement issued on Wednesday, was to propose an additional compliance test measured at 130 degrees Celsius, representing normal operating temperature, to run alongside the existing ambient test. Crucially, this new test would not take effect until August 1, 2026, meaning the first 14 races of the 24-race season would be run under the current testing regime. A vote among the five power unit manufacturers, plus the FIA and FOM (requiring a supermajority of six of the seven voters to pass), was submitted with a 10-day deadline, meaning a result was expected before Melbourne.

The politics of this resolution are fascinating. Mercedes had been legally compliant throughout, the FIA had not found any breach, and the proposed change was framed not as a retrospective correction but as a prospective clarification. The practical consequence, if the vote passes as expected, given that four of five manufacturers had been pushing for change, was that Mercedes would have from the first race in March until the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort on August 23 to use whatever advantage the thermal expansion effect provided. After that, an additional test would be enforced. Whether Mercedes would need to modify the physical engine hardware to comply with the hot test, or whether a recalibration of operating parameters would suffice, remained unclear. Either way, the championship could essentially have two distinct performance corridors: one before the summer break, and one after.

This has happened in Formula 1 before, though rarely so explicitly structured. The most famous precedent is probably the mid-season aerodynamic rule changes of 2009, when the FIA intervened to limit the double diffuser after Brawn, Toyota and Williams had clearly gained an advantage with the device in the season’s opening rounds. That intervention came after protests and FIA rulings, however, rather than through a manufacturer’s vote. Wednesday’s approach, messy and imperfect as it was, reflected a sport trying to solve a governance problem through collective agreement rather than unilateral regulation, which is at least a more inclusive process even if it leaves significant ambiguity over the first half of the season.

In the last ten minutes of the running day, the FIA undertook something genuinely interesting and practically important. Ten cars, every car except the Aston Martin whose Lance Stroll had not recovered sufficiently from his earlier adventure to rejoin, lined up on the Bahrain International Circuit’s starting grid for a procedural evaluation of a new race start sequence.

The background here is the chaotic start practice that had concluded the first Bahrain test the previous week. The removal of the MGU-H from 2026 power units removed a system that had previously been used to prevent turbo lag, filling the gap between the driver pressing the throttle and the turbocharger spooling up to full boost by using an electrical motor assistance on the turbo shaft itself. Without the MGU-H, the 2026 V6S experience genuine turbo lag at low revs, which is most acute precisely when cars are stationary on a starting grid, and drivers are trying to launch. The result was a visibly messy and unpredictable start procedure that alarmed both the drivers and the FIA’s safety observers.

The proposed modification added a second formation lap to the pre-race procedure and introduced a new visual signal: all grid boards would flash blue for five seconds before the normal red lights came on. This additional formation lap gave each car’s power unit longer to reach a stable operating temperature and MGU-K pre-charge state before launch, reducing the probability of a violent and uncontrolled wheelspin event when the lights went out. The blue-flash signal gave drivers a clear warning that the standard five-red sequence was imminent without replacing it.

The test ran cleanly. Ten cars completed the modified procedure without incident. The data went to the FIA for analysis, with a decision expected before Melbourne on whether to adopt the changes for the season opener. Given the safety implications of the original problem and the apparent lack of complications in the revised procedure, the direction of travel seemed clear. Whether the fix was sufficient or whether the starts in Melbourne would still produce excitement of the wrong kind remained to be seen.

It would be too easy and too unkind to simply catalogue Aston Martin’s difficulties on Wednesday without placing them in a framework that acknowledges what the team is genuinely attempting. The AMR26 is a car designed almost from scratch by a new lead designer in a new regulatory era, featuring a power unit partnership that was itself new for 2026 and an in-house gearbox and suspension that the team were building for the first time after years of sourcing those components from Mercedes.

Every one of those transitions, the Newey design philosophy, the Honda power unit, and the first-time suspension, represents a new source of potential issues. The fact that three of them happened simultaneously was a commercial and strategic decision made at the highest level of the organisation, presumably on the basis that a clean-sheet design had more upside than incrementally improving a car built on inherited architecture. That reasoning may well prove correct over a longer timeframe. The first pre-season, however, is going to be uncomfortable.

Stroll’s combined 26 laps on Wednesday and Alonso’s 28 represent mileage numbers that, in the context of an eight-hour test day, are essentially developmental poverty. The data that those two drivers could generate in 54 laps is a fraction of what McLaren or Mercedes were accumulating. If the AMR26’s problems are primarily reliability-related, as they appear to be, then the race pace question is even harder to answer than for other teams: you cannot fully understand where the car balances best if you cannot complete full race simulation runs.

Lance Stroll’s public comments at the first Bahrain test last week, acknowledging that the car needed more performance and more grip, were notably candid. Whether that candour reflected genuine frustration or a strategic attempt to manage expectations ahead of a difficult opening season is hard to say. What it tells you, reading his body language and listening carefully to the language used by Aston Martin’s senior personnel, is that the internal mood at the Silverstone-adjacent factory is one of controlled anxiety rather than confidence, and controlled anxiety can only be sustained for so long before it either resolves into progress or collapses into crisis.

Fernando Alonso, for his part, had said before the start of the 2026 season that the prospect of Aston Martin being competitive would make retirement a more satisfying prospect. The implication was that he would stay and fight while there was something worth fighting for. Twenty-eight laps and a 17th-place time on Wednesday was not the start of that fight he would have scripted.

Final Standings

The end-of-day results were as follows:

- George Russell (Mercedes) 1m33.459s, 76 laps

- Oscar Piastri (McLaren) 1m33.469s, 70 laps

- Charles Leclerc (Ferrari) 1m33.739s, 70 laps

- Lando Norris (McLaren) 1m34.052s, 54 laps

- Kimi Antonelli (Mercedes) 1m34.158s, 69 laps

- Isack Hadjar (Red Bull) 1m34.260s, 66 laps

- Lewis Hamilton (Ferrari) 1m34.299s, 44 laps

- Carlos Sainz (Williams) 1m35.113s, 55 laps

- Franco Colapinto (Alpine) 1m35.254s, 60 laps

- Gabriel Bortoleto (Audi) 1m35.263s, 71 laps

- Alex Albon (Williams) 1m35.690s, 55 laps

- Liam Lawson (Racing Bulls) 1m35.753s, 61 laps

- Ollie Bearman (Haas) 1m35.778s, 42 laps

- Pierre Gasly (Alpine) 1m35.898s, 61 laps

- Lance Stroll (Aston Martin) 1m35.974s, 26 laps

- Esteban Ocon (Haas) 1m36.418s, 65 laps

- Fernando Alonso (Aston Martin) 1m36.536s, 28 laps

- Nico Hulkenberg (Audi) 1m36.741s, 49 laps

- Arvid Lindblad (Racing Bulls) 1m36.769s, 75 laps

- Valtteri Bottas (Cadillac) 1m36.798s, 35 laps

- Sergio Perez (Cadillac) 1m38.191s, 24 laps

Thursday would bring Max Verstappen back to the Bahrain International Circuit for his only full day in the RB22 during the second test, Hadjar having done his day. The four-time champion had been publicly critical of the 2026 cars since his first laps in the new machine, describing them as Formula E-like and questioning whether the experience of driving them was consistent with the spirit of Formula 1. His Red Bull team principal, Laurent Mekies, had been diplomatic in response, noting that the team’s job was to build a car that Verstappen could win with, regardless of how the car initially felt.

What the data suggested was that Red Bull had work to do. Hadjar’s 1m34.260s, set in the afternoon with a recovering car after a wasted morning, was 0.801s off Russell’s benchmark. In previous regulatory eras, that kind of deficit between Red Bull and the fastest car would have prompted panic in the media. In 2026, with everyone unsure about fuel loads, tyre compounds and power unit deployment modes, it was more ambiguous. But it was not nothing.

Ferrari’s Hamilton would want a clean, uninterrupted day to finally build the kind of sustained stint data that the garage problems had denied him on Wednesday. Mercedes would be looking to extend the evaluation of the upgrade package, probably running more long-run programmes and fewer qualifying simulations. McLaren, characteristically, would probably just do whatever their programme said without deviation, which has historically been one of their great underappreciated strengths.

And somewhere in the paddock, the power unit vote would be ticking down. Manufacturers had until the following Tuesday to register their position. The five manufacturers, plus the FIA and FOM, needed to produce a supermajority of six votes for the hot-temperature compression ratio test to pass. With Red Bull having joined Ferrari, Honda and Audi against the Mercedes interpretation, and with both the FIA and FOM generally favouring regulatory clarity over competitive chaos, the outcome seemed fairly predictable. Mercedes will likely be the only manufacturer to vote against.

By the time the lights went out over Sakhir on Wednesday evening, the 2026 Formula 1 season felt both more knowable and no less complex than it had at dawn. The hierarchy at the front appeared to be resolving into something identifiable: Mercedes fast and systematic, McLaren closely competitive and high-mileage, Ferrari technically ambitious but operationally imperfect, Red Bull fast in concept but unreliable in execution.

But that reading is itself a product of one day in conditions that neither team had fully controlled or fully disclosed. George Russell was the fastest man on track by the end of the day. Ferrari may have built the most technically interesting car. The compression ratio story would follow the championship all the way to at least the Dutch Grand Prix in August. The start procedure might still catch everyone out in Melbourne.

What testing always ultimately produces is more questions alongside the data, and Wednesday at Bahrain in 2026 was no exception. The answers will have to wait for Melbourne. Eighteen days is close enough to worry about and far enough away to leave room for everything to change.